The break of trust

The break of trust with Compagnie Générale de Navigation Aérienne C.G.N.A. causes Charles de Lambert (he flew there from June until and including December 1909) to leave the airfield of Port-Aviation at Juvisy-sur-Orge, which moreover is flooded as consequence of the rising water of the Seine, and to go in search of another location to continue his activities. In February 1910 he moved his Wright machine, drawn by horses, on the road from Juvisy direction Buc, on the territory of which Louis Blériot possesses a big farm with 200 hectares of land and where he organises his airfield from 1910.

En route Charles de Lambert discovers at dark a big farm with barns belonging to farmer Paul Dautier. He asks for hospitality because his team cannot go on. He indeed finds shelter for his strange convoy ánd hospitality for himself. Next day he sees the plateau of Villacoublay, is aware of the aviation possibilities, obtains the lease of about six hectares and installs himself. Thus the private airfield of the Société de Navigation Aérienne à Villacoublay comes into being.

‘Société de Constructions Aéronautiques ASTRA’, the manufacturer of Wright-machines, sets up a new flying school in Villacoublay and engages Charles de Lambert as ‘director of flights’. Already on February 10 1910 commander Paul Renard joins him on the Wright machine for a flight of about twenty minutes, twenty five years after his first flights over Villacoublay with the balloon ‘La France’ in company of his brother Charles. Others too join in flights. On April 27 1910 (three days before Émile Dubonnet flies, with his monoplane Tellier from Issy-les-Moulineaux as second pilot above Paris) it is Ethel and Kermit Roosevelt, children of president Theodore Roosevelt who is paying a visit to Paris whereas ‘le maître des lieux’, farmer/owner Paul Dautier, gets his aerial baptism in May.

It can also be noted that on June 17 1910 Charles de Lambert makes a flight of 1 hour and 45 minutes at a speed of 65/70 kilometers an hour and that on July 27 1910 he supplies the Army Engineers, in camp Satory near Versailles, an Astra-Wright plane of a new type with an undercarriage on wheels.

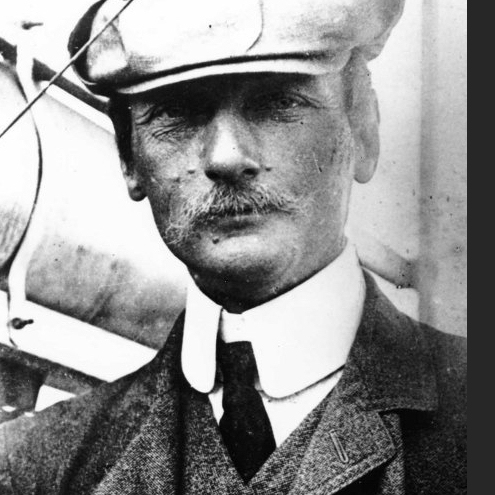

In the article ‘My Memories of Wilbur Wright’ (from U.S. Air Services of March 1935; see also figure 7-8 and figure 7-31) marchioness Cordelia M. de Lambert born Consett finally tells a ‘little story’ on the period after the glorious flight around the Eiffel Tower of her husband Charles.

Fig. 7-40

Then Charles count de Lambert returns from aviation to the navigation on water. He foresaw that the problem of navigation with an hydroplane with air propeller would have been solved quicker than that of the conquest of the air. “I have very mistaken” he says a journalist of ‘Miroir des sports’ according to an article of October 22 1929, “aviation has advanced with giant strides, whereas the hydroplane, practical means of conveyance for the streams of the colonies with small depth and even for the Rhône and the Loire, has earned only imperfect civil right in France.”

After the Wright-flying school in Pau counted 76 trainees in the winter of 1909-1910, the director of it, Paul Tissandier, for want of trainees and at odds with the ‘Compagnie Générale de Navigation Aérienne C.G.N.A.’, announces on March 16 1910 that the school will be closed. Together with his friend Charles de Lambert he continues, as commercial partner, the production of hydroplanes. In Chapter 5 CHARLES DE LAMBERT BRILLIANT INVENTOR, UNFORTUNATE INDUSTRIALIST the reader has already learned the ultimately unfortunate end of their return to the old love.

Wright biplanes converted into seaplanes also are developed by Charles de Lambert and these exploits make the international press.

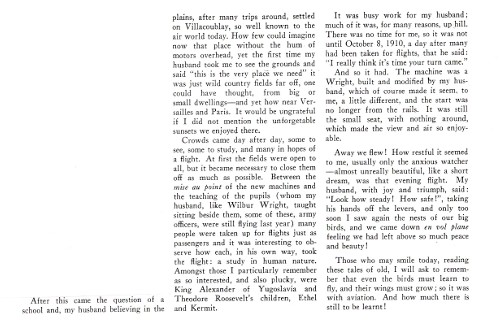

Fig. 7-41

On February 13 1913 count de Lambert leaves Triel-sur-Seine, where the hangar of his oiseau artificiel (artificial bird) is situated and, following the course of the Seine, he lands at Billancourt. Two days later at half past seven in the morning Count de Lambert, wanting to use the fine weather, is to leave by seaplane Issy-les-Moulineaux (however in the catalogue of 1982 of the exhibition ‘ISSY berceau de l’aviation’ Charles de Lambert, except for a an added entry, does not appear) to return to Triel-sur-Seine. In spite of the sun a strong wind is blowing and the machine shakes heavily. Flying above the surface of the water at a height of seven or eight metres only, Count de Lambert decides to land on the Seine. Approaching the viaduct of Auteuil and with the intention to flow underneath the central arch, he suddenly notices a tug boat pulling several barges. Without a moment of hesitation count de Lambert tries to climb to fly over the bridge but the machine does not react quickly enough on the rudders. In order to prevent a crash on the stone parapet of the railway line above the footbridge, Charles de Lambert suddenly pulls out but the tail of the machine bumps against telegraph lines, gets entangled after which the machine crashes onto the road from a height of ten metres. The airplane has partly been wrecked but fortunately the pilot, to the astonishment of spectators, rises smiling and practically without scratch. A quarter of an hour later he returns home by car. The wreck is removed on a lorry and a little group of workmen is sent to repair the broken telegraph lines.

As stated before Charles de Lambert has been constructing ‘hydroglisseurs’ up to 1931 (he is then 65!). About three years later – but fortunately before ‘Société Anonyme des Hydroglisseurs de Lambert’ is officially declared bankrupt on February 19 1941 – on November 17 1934 he is drawn out of his solitude. This on account of the twenty fifth anniversary of his flight around the Eiffel Tower. It is no longer the slender and alert man of forty but an old and melancholy gentleman the journalists come and interrogate. They ultimately discovered him in a suburb – cheaper for his purse – in villa ‘La Lorraine’ at Vaucresson, France.

Fig. 7-42

Visiting card

Fig. 7-43

Fig. 7-44

Fig. 7-45

Villa “La Lorraine”

Vaucresson (S. & O.)

November 2008

In the town hall of Paris a reception is held in his honour. The newspaper ‘Paris-Midi’ reports on it with a picture of a worn out man who exerts himself to be straightbacked. “The most well known of the old age, escorted by Mrs Watteau and Miss Deutsch de la Meurthe, are there to welcome him.” Mr. Contenot receives him in the name of the town council and hands him the Rosette of the Legion of Honour. With tears in his eyes the marquis, whose daughter tries in a corner to wipe her tears, answers to the speeches: “I had sent a little note to my mechanic who took such good care of the engine of my machine enabling my flight Juvisy-Paris and back, well I do not see him, he will not be able to receive part of the congratulations, it makes me very sad.”

On this occasion Charles de Lambert still declares: “From the age of eighteen years I am following this saying of Paul Painlevé” – mathematician and politician who in 1907 convinced the House of Representatives on the necessity of military aviation –

GIVING WINGS TO THE WORLD

It will be the last time the public will hear on Charles, marquis de Lambert. Still ten long, too long years to live, remain. From 1931 marquis de Lambert is ruined, irretrievably ruined, one cannot even compare his situation to that of his grandfather’s who could at least end his days in dignity. Even Charles de Lambert does no longer possess the essentials to maintain his own family.

Certain members of the family are not warned on his distress, his dignity is that great, others remain indifferent to his tragic fate. Others in the end, shamed or disdainful, pretend not to know it: in his family only remembrance of him remains. It is the merit of his brother-in-law married to Winifred Edit Consett, Louis count de Boisgelin, who during twenty five years, until the end of the generation, takes care for the survival of Charles de Lambert, of the marchioness and of the unhappy Daysie.

Mrs Tissandier, wife of Paul Tissandier, explained “La Lorraine had to be left for a miserable private boarding house at Versailles”. On the remark that the end of the life of de Lambert became very sad due to the almost miserable situation he found himself in she answers: “Mrs de Lambert who did make confidential remarks never has given me any inkling in this direction. The de Lamberts have never made any appeal to us for their daily needs, because the debt owned my husband was entirely business.” May 31 1974 she writes: “The last memory I have on them is a visit I have paid them, without knowledge of my husband, because Mrs de Lambert had been an unforgettable girl-friend for me. I met them in a very modest private boarding house in Versailles, ill, piteous, I have gone away with a very sad heart.”

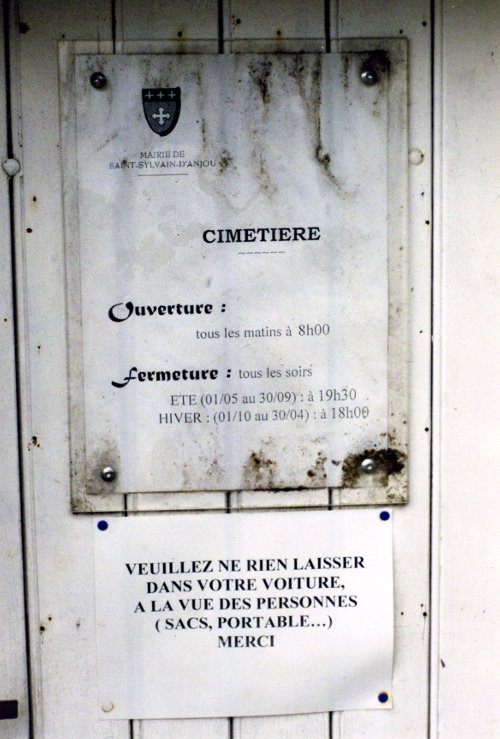

No doubt the circumstances during the occupation in the Parisian suburbs, are still more injurious to their health. Probably it is count de Boisgelin who finds a resort for them in a ‘Maison de Santé pour maladies Mentales et Nerveuses’ in the not very brightening old castle ‘Château des Grullières’, not far from Saint-Sylvain d’Anjou (near Angers) in Maine-et-Loire for which he bears the expenses of their stay.

Fig. 7-46

Fig. 7-47

Private house of director, head-physician, at entrance of park

‘Château des Grullières’

Saint-Sylvain d’Anjou

Wednesday July 2 2003

Fig. 7-48

One of the pavilions of the patients, nowadays furnished apartments

‘Château des Grullières’

Saint-Sylvain d’Anjou

Wednesday July 2 2003

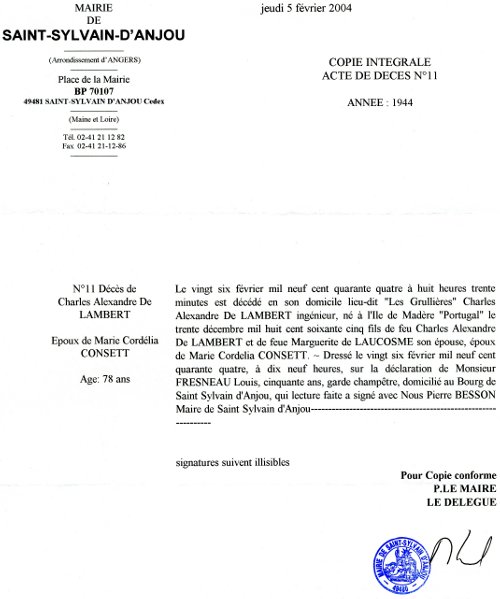

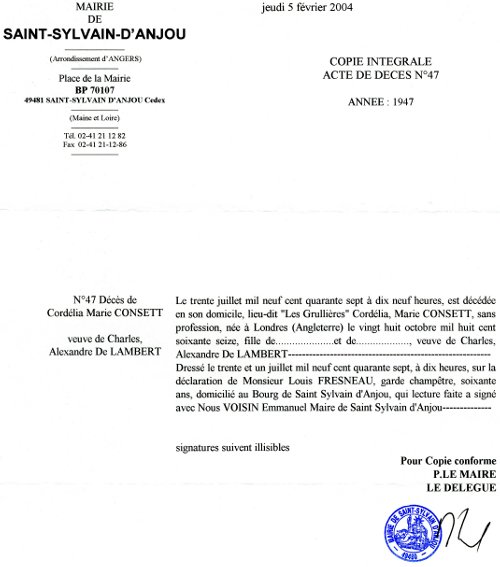

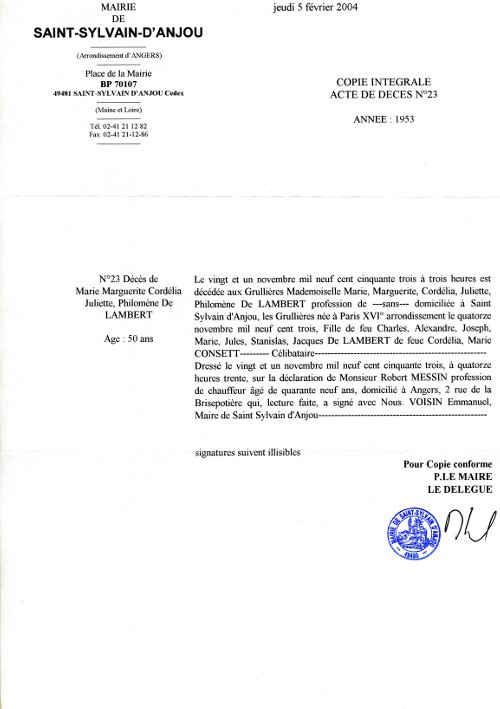

The marquis dies of a bladder-ilness on February 26 1944 at 08:30 o’clock, the marchioness on July 30 1947 19:00 and finally Marguerite on November 21 1953 03:00 o’clock.

Fig. 7-49

Fig. 7-50

Fig. 7-51

In spite of the post war conditions it is certain Louis count de Boisgelin who succeeded in sending an amount of money to abbot Masson, parish priest of Saint-Sylvain d’Anjou in order to assure a proper burial place of the marquis. Abbot Masson, transferred, disappears without having fulfilled his duties. Did he or did he not receive the remittance, one does not know. In 1974 only an insignificant little mound was left, not a cross nor any other indication.

Fig. 7-52

Fig. 7-53

Dreariness with abandoned graves on the graveyard at Saint-Sylvain d’Anjou

Wednesday July 2 2003

What a beautiful epitaph would have been the device of the marquis:

GIVING WINGS TO THE WORLD