Seguin

By purchases effected in 1901, 1902, 1904 and 1912 Charles de Lambert is for the greater part owner of the island Ile Seguin situated in the Seine in Paris. On June 24 1919 he lets by contract his possessions for twenty nine years and nine months to Louis Renault against payment of an annual rent of 40.000 francs for each of the first four years, and 45.000 francs for each of the remaining years.

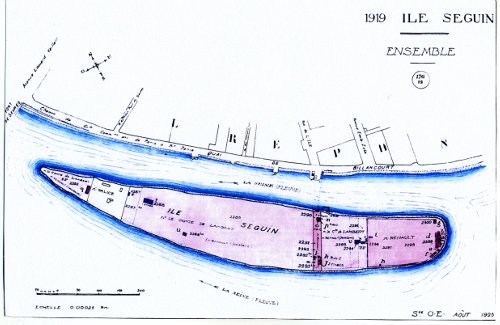

Fig. 5-18

Sketch of the situation Ile Seguin

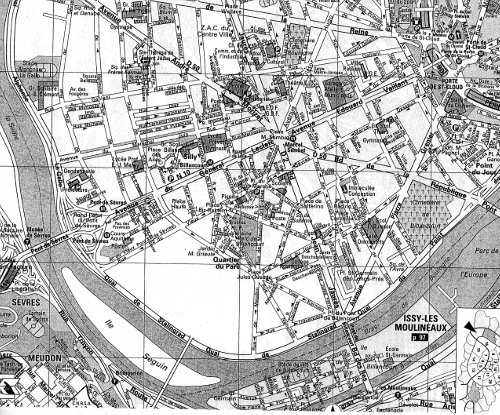

Fig. 5-19

Plan of the owners of Ile Seguin in 1919

His advisers urge de Lambert to sell the island, but he sustains doggedly. Can’t he do without his ball-trap (clay-pigeon shooting) there? In the end he sells 83.158m² to Louis Renault for the price of 1.300.000 French francs on June 6 1923. In January-February 1910 and in February 1911 the island was flooded which causes Louis Renault to raise the level of the island with six meters of concrete. Hereafter demolition will be difficult.

The plot in Nanterre - town where on March 21 1923 a fire reduced the work-shops of Charles de Lambert to ashes and the roof collapsed – is property of a certain Mrs Heudebert from Vésinet, who asks 100 French francs a square meter. De Lambert takes an option on it with money of Tissandier, cannot raise the funds for the purchase, after which it is count de Boisgelin who mediates, reselling to Charles de Lambert of his option, on the basis of 40 francs per square meter.

Paul Tissandier has no longer a franc to help his friend who owes him a total of 210.000 French francs as principal and interest at a rate of 10% (actual bank rate at the time), but one credit company after the other refuses funds because of lack of surety such as mortgages already encumber the existing plants. The interest on the loan contracted with Tissandier is paid only in 1927. In 1931 the accumulated interest and principal sum owed by Charles de Lambert to his obliging partner amounted to 239.000 francs.

In spite of the financial difficulties Charles de Lambert continues to build hydroplanes until 1931, so until his 65th . In this way about fifteen every time faster, bigger and more comfortable models are developed. The latest model laid down and sold, had a composed hull with resistance-reducing gaps and was equipped with a Renault motor of 450 HP. With forty persons on board it reached 80 km/h.

Even on December 18 1974 Mrs Tissandier wrote to a French investigator: “I will not tell you on the troubles which resulted from this unfortunate co-operation”. Some bills of Paul Tissandier, written in pencil; rough drafts of increasingly more pressing letters which emphasize the financial needs of Tissandier, have been given by his widow to the historian. From this one can judge what must have been the torment of this man, forced to get back his own money, but also careful to keep the friendship, the undamaged admiration which he is entertaining for his elder one whose financial problems he knows. Their intimacy is such that Charles de Lambert is godfather of Anne-Marie Tissandier born in 1920.

Paul Tissandier lacks the courage to trouble his debtor, until yet he decides to do so in a letter dated December 4 1928; a second time on March 1 1929, but rather appealing than summoning: “You would render me a real service if you would remit me a small payment on the rent you owe me.”

From that moment they quarrel. For sure they correspond with de Lambert, not being conscious of having done anything wrong, writes in most affectionate terms. Then, little by little, notaries and businessmen take over the action. However one aspect remains striking: Paul Tissandier either due to lack of financial means to carry it through to the end, or in ultimate deference to a man of value, perhaps at last because he estimates the uselessness of this step, has never put in a legal claim to Charles de Lambert.

Only on February 19 1941 (the sixtieth birthday of Paul Tissandier) Société Anonyme des Hydroglisseurs de Lambert is officially declared bankrupt. This after the occupying German forces had opened the safe of the company with bank Crédit Industriel de l’Ouest but in which nothing of interest is discovered. Unaware of the whereabouts of Charles de Lambert, the bankers once more contact Tissandier to…claim the salary of the locksmith and the cost of repair of the forced safe!

“I remember,” Mrs Tissandier wrote on February 9 1941, “one day my husband told me he had received a letter of a notary public to inform him he had lost everything…”.